ALTCULTURE MAGAZINE●63●11/2022●POOLOURI adică Paranoia Schwartz (XVII)

De Gheorghe Schwartz

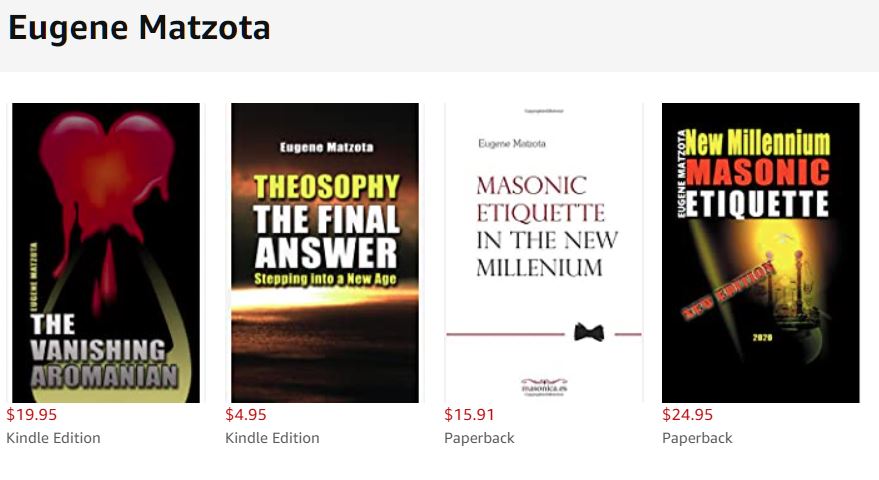

Tradus de / Translated by Eugen / Eugene MATZOTA

ECOULTOUR le mulțumește tuturor celor care sunt alături în lupta pentru educație și cultură!

POOLOURI adică Paranoia Schwartz

sau

pildele cele mai însemnate din viața plină de învățăminte și îndrăzneală a preacinstitului și prealuminatului Gough, precum și a nu mai puțin strălucitului său contemporan Finch, cu precizări asupra modului în care înțelepții de ieri, de alaltăieri și dintotdeauna au știut să răsfrîngă aceste întâmplări în subtilele lor maxime și cugetări. Și asta nu este încă nici pe departe totul…

CARTEA A PATRA

în care se dovedeşte încă o dată că dragostea este un lucru mare, arătându-se în acelaşi timp şi primejdiile ei de netrecut cu vederea, precum şi învăţămintele ce trebuie trase din aceste împrejurări, aşa cum bine au făcut şi înţelepţii lumii de ieri, de alaltăieri şi dintotdeauna, atunci când au formulat, pe baza pildelor lui Gough, subtilele lor cugetări

Ce ne spun documentele vremii?

“Gough o sărută cu o nespusă duioşie pe Poyy pe frunte.”

(Afirmaţia revine de opt ori în “Amintirile sentimentale ale domnului Gough”, apărute la Baga în ediţie postumă, nedatată.)

De Gheorghe Schwartz

Tradus de / Translated by Eugen / Eugene MATZOTA

Telefoanele

“De zece ori pe zi trebuie să te învingi pe tine însuţi.” – Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 1, p.37.

El – Gough – ştia că ea există şi, lucru mai important, ştia şi unde se află. Se părea că nimic nu se poate pune în calea fericirii lor. N-avea decât să-i dea un telefon. Aşa că formă numărul.

În timpul acesta – cum se întâmplă de atâtea ori între îndrăgostiţi – şi Ea se gândea la El. Îi putea vorbi, lucru pe care-l dorea nespus de mult. Se instală lângă telefon pe o pernă moale, aşezată direct pe parchet, şi se pregăti cu nesaţ pentru o convorbire pe care o voia cât mai lungă. Formă numărul.

Dar, fiindcă sperau atât de mult să-şi vorbească, ridicară receptoarele în acelaşi timp şi de aceea, la capătul celălalt al firului, telefonul indica mereu “ocupat”.

Şi n-au pus nici unul receptorul la loc, fiecare dintre ei formând iar şi iar numărul atât de dorit şi neprimind altă răspuns decât mereu “ocupat”, în minţile fiecăruia dintre ei ciuda începu să fie înlăturată de gelozie, apoi de revoltă: când tu doreşti din tot sufletul să auzi vocea celui drag, acesta de ce discută cu cine ştie cine?

Au încercat amândoi ore în şir să-şi vorbească şi, pentru că n-au reuşit, pasiunea lor s-a stins în acelaşi timp şi au pus amândoi deodată receptorul în furcă.

Acum ar fi putut vorbi oricât ar fi dorit unul cu celălalt…

O dată, peste ani, formând greşit un număr, i-a răspuns Ea:

– Cred că aţi greşit numărul, i-a spus, fără să-şi amintească vocea lui.

– Vă rog să mă scuzaţi, i-a răspuns El, fără s-o mai recunoască.

Nevoia de obiecte

“Adesea singurul leac al durerilor noastre constă în uitare; dar noi uităm leacul.” – (Gracián, Or., 262.)

Gough avea o iubită care credea cu convingere în el. Când erau împreună, se vedeau doar unul pe celălalt şi ignorau mulţimea de obiecte din jur.

Dar când îi pleca iubita, Gough trecea prin momente grele: pierdea tot (şi mereu lucruri de care avea neapărată nevoie). Era de-a dreptul disperat şi oferea un spectacol jalnic celor din jur cu panica sa continuă. Găsea întâmplător un obiect? Pierdea imediat altul. Nu mai putea lucra, nu mai putea ieşi în lume, nu se mai putea descurca deloc: rătăcea paltonul, rătăcea ochelarii, rătăcea lingura în timp ce mânca (şi se scula să caute altceva), îşi pierdu într-o zi până şi patul din casă.

(Asta s-a întâmplat cam aşa: se trezise brusc, după ce în vis – ca urmare a unei preocupări intense din timpul zilei – i se arătase aparatul de bărbierit, rătăcit cu vreo săptămână în urmă. Se făcea că aparatul respectiv se afla sub covorul mare din sufragerie. Cum a ajuns acolo, Gough renunţă să se mai întrebe. Mută, deci, toate mobilele de pe covor în dormitor, iar pe cele aflate aici le împinse spre debara.

Din păcate, sub covor nu găsise decît costumul negru şi actul de naştere, pe care le rătăcise mai demult. Tot împingând când un dulap, când un scrin, când o canapea, mai dădu de o seamă de lucruri ce îi dispăruse deja din memorie. Aparatul de ras, bineînţeles, nu-l găsi. Apoi mută totul la loc. Cu excepţia patului. Care parcă s-ar fi topit.)

Era o situaţie atât de neobişnuită, încât nu-l crezu nimeni. Nici măcar iubita sa, care ţinea foarte mult la el, şi pe bună dreptate, pentru că altfel era un om integru, virtuos şi inteligent. Îl aprecia atât de mult, Doamne, cât îl aprecia!

Până la urmă, trebui să recunoască şi ea că doar amorul lor nebun îl făcea pe Gough să nu mai aibă nevoie de nimic atunci când erau împreună. Însă când era singur… Aşa că, în continuare, au avut grijă ca dragostea lor să ardă mai domol, spre a putea vedea obiectele ce le lipseau, gândindu-se ei că dragoste, dragoste, dar mai trebuie să fii şi prevăzător, din iubire nu se poate trăi la nesfârşit. Şi au început să caute din nou, amândoi împreună şi fiecare în parte, tot ce le lipsea.

Căsătoria

“Cel mai drept şi cel mai destoinic este acela care împarte răsplata cea mai mare celor mai vrednici.” – (Democritus, la Diels, fr. 263.)

La nunta fiului său, doctorului Gough îi fu dat să asiste, împreună cu toţi cei de faţă, la un spectacol straniu:

– Edgar Gough, întrebă preotul, vrei s-o iei în căsătorie pe…

– Edgar Gough sunt eu, se repezi mirele fericit.

– Edgar Gough, vrei să…, vru să reia preotul.

– Edgar Gough sunt eu, răspunse inoportun mirele cu aceeaşi voce piţigăiată.

În această fază a evenimentului, se strecură o clipă de tăcere. Asistenţa şoptea plină de bunăvoinţă: “Edgar Gough, vrei să iei în căsătorie pe…”, iar Edgar Gough răspundea tot în şoaptă, însă piţigăiat: “Edgar Gough sunt eu”.

– Ştiţi, mie nu mi se pare important să precizez acest lucru într-un moment atât de solemn, pentru că altfel ar putea să se dea oricine drept mine şi să se însoare în locul meu.

– Dar te cunosc, fiule, de când erai mic…

– M-am mai schimbat de atunci.

– Bine, dar sunt de faţă, părinţii tăi, rudele…

– Ei, da! Să zicem că eu sunt în regulă. Dar dumneata cine eşti?

– Eu sunt preotul care te va cununa, Edgar Gough.

– Cum vă cheamă? Ştiţi, e bine de spus totul. Până nu e prea tîrziu.

– Eu sunt abatele Henric Krupa.

– Henric…, repetă gânditor Edgar Gough. E bine, mătuşică, să te cunune un preot care se numeşte Henric?

– Pe mine m-a cununat abatele Gheorghe Krupa. A murit în 1914.

– Atunci e mai bine să-l cheme Henric, aprobă repede Edgar Gough. Henric… Henric…

– Numele ăsta îl am de la tata, se pomeni abatele spunând plin de mândrie.

– Şi celălalt?

– Care celălalt?

– Păi, ziceaţi că vă cheamă şi Krupa. Sau mă înşel? Părinte, dacă problema asta vă e penibilă, am putea să discutăm între patru ochi. Hai, copii, ieşiţi puţin să admiraţi cimitirul comunal!

Rămaşi singuri, abatele Krupa se simţi brusc stânjenit. O vreme, domni liniştea.

– Între noi n-ar trebui să existe tăcere, spuse, în sfârşit, Edgar Gough.

– Ţi se pare că nu e ceva în regulă?, îl întrebă abatele.

– Să nu ne grăbim cu concluziile! Să nu ne grăbim cu concluziile!

– Atunci?

– Adevărul e că nimănui nu-i e scris pe frunte ceea ce este şi în ce scop este ceea ce este.

– Mă cunoaşte tot orăşelul!

– Dar nu te cunosc eu! De altfel, nu-l cunosc nici pe brutar, nici pe măcelar şi nu-mi cunosc nici lăptăreasa. Dar îi cred fiindcă şi ei tot aşa zic: că-i ştie tot orăşelul… În fine, de ce să-mi fie ziua nunţii altfel? Şi acum, ce-i cu dumneata, de ce te-ai ruşinat?

– Ai făcut un gest urât! Nu trebuia să-i dai afară! Să-ţi trimiţi mireasa în ziua nunţii în cimitir…

– Toţi ajungem acolo, suspină Edgar Gough.

– În cimitir e multă lume, spuse naşul, în timp ce se întorcea cu ceilalţi în biserică.

– Îl aşteaptă pe abate la o înmormântare, spuse socrul mare.

– Se face frig, vine iarna, mai spuse cineva.

– Să ne grăbim, spuse Edgar Gough.

În continuare, ceremonia a decurs normal.

Ultimii de pe Gulliver

“De aceea, cel care leagă pe veci, să cerceteze dacă inimile sunt de acord! Iluzia este scurtă, căinţa lungă.” – (Schiller, Lied, 8., 4.)

Gough, rătăcit prin părul lui Gulliver, făcu o faptă bună. Atunci veni zâna cea frumoasă şi-i făgădui îndeplinirea a trei dorinţe.

Gough o rugă să-l scoată la lumină, să-i dea un măr să-l mănânce şi o fată să-l iubească.

Într-o zi, hoinărind prin livada sa, la braţ cu Poyy, Gough, văzând o liană înaltă ce se căţăra pe copaci, îi povesti fetei cum a bâjbâit el prin părul lui Gulliver, cum vâna acolo puricii cu lancea şi cum se descurca de minune prin mlaştinile de mătreaţă. Apoi, a doua zi, îi vorbi despre întunericul plin de romantism şi de mister din părul uriaşului. Şi-i povesti şi a treia zi, şi a patra zi.

O dată, făcând şi Poyy o faptă bună, veni iarăşi zâna cea frumoasă şi-i făgădui împlinirea a două dorinţe. Poyy o rugă s-o ducă în părul lui Gulliver şi să-i dea voie să-l ia cu ea şi pe Gough.

În părul uriaşului, cei doi au dus-o greu. Gulliver începea să chelească şi de aceea îşi îngrijea părul cu fel de fel de loţiuni ce îl îmbolnăveau pe Gough de reumatism, iar Poyy contractă o aprindere de plămâni.

Şi, făcînd ei împreună o faptă bună, veni din nou zâna cea frumoasă să le promită îndeplinirea unei dorinţe. Însă ei, bolnavi şi bătrâni, fiindu-le teamă să nu vor putea birui o călătorie lungă, dar neavînd nici ce spera în duhoarea şi întunericul din părul lui Gulliver, n-o mai rugară pe zână nimic. Iar dacă mai făceau fapte bune, le făceau discret şi seara se duceau pe întinderea unde uriaşul începea să chelească mai tare şi de unde puteau privi luna şi stelele.

Doar o singură dată o mai rugară pe zână să le mai satisfacă o dorinţă, iar zâna veni şi le mai primi rugămintea şi-i lăsă să moară împreună. Ei au fost ultimii oameni din părul lui Gulliver: Gough şi Poyy, un bătrîn reumatic şi o femeie ce tuşea mereu.

Apoi zâna cea generoasă îi acoperi cu mătreaţă şi plecă altundeva, să răsplătească şi acolo oamenii cei buni.

POOLOs namely Schwartz Paranoia

or

the most important parables of the life full of learning and boldness of the pre-eminent and pre-enlightened Gough, as well as of his no less brilliant contemporary Finch, with details on how the sages of yesterday, of the other day and always knew how to reflect these events in their maxims and thoughts. And that’s not all yet…

FOURTH BOOK

which proves once more that love is a great thing, while showing at the same time its dangers which cannot be overlooked, and the lessons to be drawn from these circumstances, as the wise men of the world of yesterday, the day before, and always have done, when they have formulated, on the basis of Gough’s parables, their subtle sayings

What do the documents of the time tell us?

„Gough kisses Poyy on the forehead with an unspeakable dutifulness.”

(The statement recurs eight times in „Mr Gough’s Sentimental Memories, published by Baga in a posthumous, undated edition.)

De Gheorghe Schwartz

Tradus de / Translated by Eugen / Eugene MATZOTA

The Phones

„What can’t two people who agree achieve?” – (Somadeva, Kath., 5, 12.)

He – Gough – knew she existed and, more importantly, knew where she was. It seemed that nothing could stand in the way of their happiness. All he had to do was give her a call. So he dialed the number.

All the while – as so often happens between lovers – She was also thinking of Him. She could talk to him, something she wanted very much. She settled down next to the phone on a soft cushion, sitting directly on the floor, and eagerly prepared herself for a call she wanted as long as possible. He dialed the number.

But because they hoped so much to talk to each other, they picked up the handsets at the same time, and that’s why, on the other end of the line, the phone always said „busy”.

And neither of them put the receiver back, each of them dialling again and again the number they wanted so much and receiving no answer other than always „busy”, in the minds of each of them the strange began to be overcome by jealousy, then by revolt: when you want so much to hear the voice of your loved one, why does he talk to who knows who?

They both tried for hours to talk to each other, and because they couldn’t, their passion fizzled out at the same time and they both suddenly put the receiver back in its holder.

Now they could talk as much as they wanted with each other…

Once, over the years, dialing the wrong number, she answered him:

– I think you got the wrong number, she told him, not remembering his voice.

– Please excuse me, He replied, without acknowledging her.

De Gheorghe Schwartz

Tradus de / Translated by Eugen / Eugene MATZOTA

The need for Objects

„Often the only cure for our sorrows lies in forgetfulness; but we forget the cure.” – (Gracián, Or., 262.)

Gough had a girlfriend who believed in him with all her heart. When they were together, they only saw each other and ignored the crowd of objects around them.

But when his girlfriend left, Gough had a hard time: he lost everything (and always things he desperately needed). He was downright desperate and made a sorry spectacle of himself to those around him with his constant panic. Had he found something by chance? He’d immediately lose another. He couldn’t work, he couldn’t go out, he couldn’t manage at all: he misplaced his coat, he misplaced his glasses, he misplaced his spoon while eating (and got up to look for something else), he even lost his bed in the house one day.

This went something like this: he had woken up suddenly, after in a dream – as a result of intense daytime preoccupation – he had been shown his razor, misplaced a week or so before. The razor happened to be under the large carpet in the living room. How it got there, Gough gave up wondering. So he moved all the furniture on the carpet into the bedroom, and pushed the furniture there into the closet.

Unfortunately, all he found under the carpet was his black suit and his birth certificate, which he had misplaced earlier. Pushing a cupboard, a chest of drawers or a sofa, he found a number of things that had already disappeared from his memory. The razor, of course, he couldn’t find. Then he moved everything back. Except the bed. Which seemed to have melted.)

It was such an unusual situation, no one believed him. Not even his girlfriend, who was very fond of him, and rightly so, because otherwise he was a man of integrity, virtue and intelligence. She appreciated him so much, my God, as she appreciated him!

After all, she would have to admit that their mad love alone made Gough want for nothing when they were together. But when he was alone…

So they kept their love burning more gently, so that they could see the objects they were missing, thinking that love, love, but you also have to be careful, out of love you can’t live forever. And they began to look again, both together and each separately, for what they were missing.

De Gheorghe Schwartz

Tradus de / Translated by Eugen / Eugene MATZOTA

The Marriage

„Therefore let him who binds forever, let him search whether hearts agree! Illusion is short, repentance long.” – (Schiller, Lied, 8., 4.)

At his son’s wedding, Dr. Gough witnessed, with all present, a strange spectacle:

Edgar Gough, asked the priest, will you marry…

Edgar Gough, it’s me, the happy groom rushed in.

Edgar Gough, will you…, the priest wanted to repeat.

Edgar Gough, it’s me,” replied the groom in the same piqued voice.

At this stage of the event, a moment of silence crept in. The audience whispered good-naturedly, „Edgar Gough, will you marry…” and Edgar Gough whispered back, still in a whisper but with a chirp, „Edgar Gough is me.”

You know, I don’t think it’s important to say this at such a solemn moment, because otherwise anyone could pretend to be me and marry instead of me.

But I’ve known you, son, since you were a boy…

I’ve changed since then.

All right, but I’m here, your parents, relatives…

Oh, yes! Let’s say I’m okay. But who are you?

I’m the priest who’s going to marry you, Edgar Gough.

What’s your name? You know, it’s good to tell everything. Before it’s too late.

I’m Abbot Henry Krupa.

Henric…, Edgar Gough repeats thoughtfully. Is it all right, Auntie, to be married by a priest named Henric?

I was married by Abbot Henrik Krupa. He died in 1914.

Then he’d better be called Henric, Edgar Gough quickly agrees. Henric… Henric…

I got that name from my father, the abbot said proudly.

And the other?

What other?

Well, you said your name was also Krupa. Or am I mistaken? Father, if you find this matter embarrassing, we could talk in private. Come on, kids, come out and look at the cemetery.

Left alone, Abbot Krupa felt suddenly embarrassed. For a while, silence reigned.

There should be no silence between us, said Edgar Gough at last.

Does anything seem wrong to you, the abbot asked.

Let’s not jump to conclusions! Let’s not jump to conclusions!

Well?

The truth is, it is not written on any man’s forehead what he is, and for what purpose he is what he is.

The whole town knows me!

But I don’t know you! Besides, I don’t know the baker or the butcher, and I don’t know my milkmaid. But I believe them because they say so too: the whole town knows them… Anyway, why should my wedding day be any different? Now, what’s the matter with you? Why are you ashamed?

You made a bad gesture! You shouldn’t have thrown them out! Sending your bride to the cemetery on your wedding day…

We all end up there, Edgar Gough sighs.

There’s a lot of people in the cemetery, said the godfather, as he and the others returned to the church.

They’re waiting for the abbot at a funeral, said the great father-in-law.

It’s getting cold, winter is coming, someone else said.

Let’s hurry, said Edgar Gough.

Then the ceremony went on as normal.

The last People on Gulliver

„He who is most just and most worthy is the one who shares the greatest reward with the most worthy.” – (Democritus, in Diels, fr. 263)

Gough, wandering through Gulliver’s hair, did a good deed. Then came the fair fairy fairy and promised him the fulfilment of three wishes.

Gough asked her to bring him out into the light, to give him an apple to eat, and a girl to love him.

One day, wandering through his orchard, at Poyy’s arm, Gough, seeing a tall vine climbing the trees, told the girl how he had groped through Gulliver’s hair, how he had hunted there for fleas with a spear, and how he had done wonderfully through the dandruff bogs. Then, the next day, he told her about the dark romance and mystery in the giant’s hair. And he told her about it the third day, and the fourth day.

Once Poyy had done a good deed, the beautiful fairy came again and promised him two wishes. Poyy begged her to take her to Gulliver’s hair, and let her take Gough with her.

Into the giant’s hair the two took her hard. Gulliver was beginning to go bald, and so he groomed his hair with all sorts of lotions that made Gough sick with rheumatism, and Poyy contracted a lung inflammation.

And, they having done a good deed together, the fairy fairy came again to promise them the fulfilment of a wish; but they, sick and old, fearing they might not be able to conquer a long journey, but having no hope in the stench and darkness of Gulliver’s hair, asked the fairy nothing more. And if they did any more good deeds, they did them discreetly, and in the evening they went to the stretch where the giant began to call louder, and from where they could watch the moon and stars.

Only once more they asked the fairy to grant them a wish, and the fairy came and granted their request and let them die together. They were the last people in Gulliver’s hair: Gough and Poyy, an old man with rheumatism and a woman who always coughed.

Then the generous fairy covered them with dandruff and went off somewhere else, to reward the good people there too.