De Nicholas Jordan

Încerc să-l restitui literaturii române pe acest mare scriitor, cum spun nu doar eu, ci și nume mari. Marin Sorescu, Romul Munteanu, Fănuș Neagu sau George Pruteanu, folosesc cuvinte extrem de elogioase vorbind despre Omul de cenușă, Ashman în original, un roman informațional scris în anii 1988-1992, publicat în 1993, zece ani înainte de răspândirea Internetului și de apariția lui Google.

Marin Sorescu îl compara cu Umberto Eco iar Fănuș Neagu spunea c-așa ar fi scris Îngerul a strigat, dac-ar fi vrut să-l publice întâi în SUA. Din păcate, viața a fost prea dură cu el…

Intrat în bătaia puștii care țintea un anumit fost președinte al României, n-a fost lichidat la propriu, dar s-a mers până la o pretinsă înmormântare a sa înainte de 1993, când apare în imaginile de la lansarea cărții, ba s-a insinuat c-ar fi mult mai întunecat la culoare.În poza din stânga se vede că este cam viu pentru unii, dar asta-i altceva.

L-am convins să-mi dea permisiunea de a publica un fragment dintr-o carte încă neterminată: TURNUL.

O public cu același respect ce-l port de aproape 30 de ani pentru marele scriitor ce pare pierdut în acest război ce nu este al lui, cu ocazia împlinirii vârstei de 72 de ani.

Vă invit să vă delectați cu textul care urmează. Merită, zău așa!

Eugen Matzota

16. IN MEMORIAM: Fiecare dintre cei șase prieteni așezați în cerc la taifas își reamintește cu totul altfel momentul sosirii sale la Ierusalim pe calea aerului

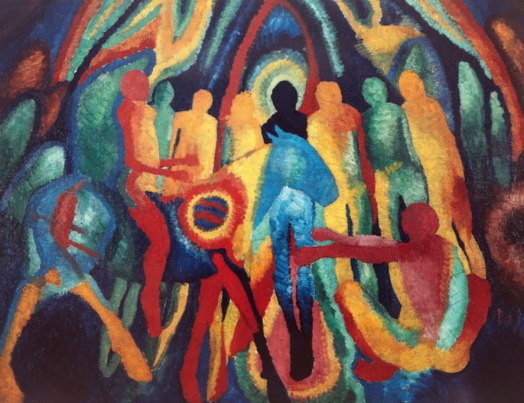

Tabloul lui Wilhelm Morgner, „Intrarea lui Isus în Ierusalim,” din 1912, prevestește că el ar fi putut deveni un mare pictor abstract, dacă nu murea în plin război, în 1917

THE TOWER

“I wrote this long story, The Tower, a mini-novel of sorts, because all I want, symbolically, is to remain inside a tower forever.”

“I wrote it because, contrary to what everyone else around me had done—running from yet another massive tower, not the first one, of course, but, let’s say, a really massive tower totally in flames. I had chosen to stay inside. Someone had to rescue the five sick lab animals locked somewhere up, inside the labyrinth of corridors on the second floor.”

“I wrote it because I had been obsessed since childhood to show the others The Way, regardless of its direction or its consequences. I wrote it because I aimed to be the first to scamper out of the tower, sliding, for example, on a flimsy rope—to the left, to the right, the direction didn’t even matter. I would have climbed straight back up, if needed, with only one condition though, to lead the others toward salvation the manner I saw fit and alone.”

As I had already discovered during the years we spent together at the university, not just one, but all of my friends knew better than me what made me tick, or rather made me write, better yet, they knew exactly even to whom I had addressed every word in all my previous writings—in their mind, I had identified my would-be readers long time ago, since the very beginning, actually.

No one had thought to offer me a much simpler, and truer, motivation: I wrote so much because I liked to. I wrote to prove that, just by myself, I can put together a coherent structure, with a start and an ending, a structure sprouting from the ground out of nothing and yet climbing slowly toward the sky without any visible support, but the pages accumulating one over the other. A diaphanous paper cathedral.

What struck me as truly odd this time around, was their fully-built opinion, offered to me with such assurance, and yet relying only on what I’ve told them by phone that I was contemplating as the subject for my next book. All that deep thinking kept coming from other friends as well, when, at that very moment, I had completed, at best, ten pages.

I decided to change the title. I wouldn’t want a potential reader’s attention wandering up the wrong path. ” ‘The Princess and the Tower’ sounds better,” I thought, “A sensible title for any generic children’s story, especially this one, addressed as it is to the vulnerable teenage girls of today.”

Without any effort, I had just stumbled upon a better title, one which sounds a lot more plausible than just “The Tower,” my somewhat monastic first iteration. By then, I wasn’t even sure how I had reached my choice. “From the moment you turn the first page, the Princess is the protagonist, not the Tower. And then, of course, there comes the Big Thistle, which, although nothing but a scrawny sprout at that stage, still, it has far more impact than the Tower for a while. There is another, obvious difference: The Thistle speaks a lot, much, much more than the Tower, which is rather taciturn.

My friends still attached the old me and figured they knew what I would have used as motivation. I am not as obsessed with towers as they imagine. Most towers, everyone knows, are massive structures in which hordes of people live vicariously at different levels on a permanent basis, or, if no one is living inside, large groups of strangers gather from the streets and climb for an hour or two to the top terrace, run aimlessly around during that time and take a million pictures. There’s always a few, who spit over the railings, and then lean over quickly, trying to guess the spot where their saliva will be landing.

I am different. I value solitude. That’s why I was more interested in what Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix call a watchtower—the idea in itself, a special one, as slim as possible, with adequate space, but spartan quarters at the top, just a few chairs and a table, no other furniture. Actually, I even had one built three years ago, using my last serious money. Approximately built.

„I’m going to serve only the regular kind today,” I told them as we sat down at the long table edging the left side of the terrace. Today, the scratched slab of faded redwood on the top was covered all over with neatly printed pages, each one criss-crossed in places with small notes on the margins. „Nothing else seems to work in this house but the coffee maker. I think I might have enough for three coffees each. Then we’ll start in earnest.”

They all shook their heads languorously, three of them shrugged. Like giant wind-up toys, they had remained in unison at all times and still kept nodding, as if in complete agreement. “Sure,” they seemed to say. “Only regular. Three, two, one. Zero. How many they may drip. We really didn’t expect anything from you today, and definitely, not coffee made in the sand. No way, sir. That’s not who we are.”

If I wasn’t able any longer to entertain my guests in the same extravagant style I used to three or four years ago, at least something which couldn’t be priced had not changed: the unobstructed all azimuth view from the terrace of my house, replete with its unreal atmosphere of peace, which everyone eventually notices.

In front of us, gulls, cormorants, and the occasional sea eagle swarmed through the air, taking turns in plunging straight down to the ocean surface, each one following their unique specialization: either they plunged further and disappeared instantly from sight, or they changed the angle of attack at the last second, skimming the waves for a long time, until they suddenly rose straight up, as if an unseen creature threatened to pluck them from the air by their tails. Up there, as if an urgent order had just reached them, they quieted at once and they’d start intermingling lazily with their brethren already at their place in the high flying mothership formation. The soundless sky dance in the heavens carried on and on and in all its indifferent splendor never skipped a beat. I knew nothing really mattered, everything stayed lost within that Grand Design without a beginning or an ending.

Surprisingly for me, none of my friends was watching the seabirds. Their eyes were riveted by something behind me, somewhere to the right. I didn’t need to turn my head and twist a stiff neck already damaged beyond repair to find out.

For a month or so, a flock of sea swifts would swirl every morning across the narrow corridor between the back of the house and the sharp, snow-covered peak of Mount Great. In just a few seconds, the swifts had already reached the forest on the right, its trees surprisingly still, as the cold wind which had begun to blow out early in the morning kept wnistling over the treetops.

Then the birds disappeared, but I knew roughly where all of them were: flying low and spreading around to hunt insects, feeding continuously like there was no tomorrow. Soon, two dozen were clinging upside on the white fence of the watchtower to quietly assemble sticky dollops of regurgitated goo, a daily staple for the chicks waiting up in the nests.

I was sure my friends had no idea what kind of birds they had been looking at for the last half a minute. I waited patiently to see what they were up to, but the reverse was valid as well: they were observing me in the same manner, a dogged patience on display for all. I was sure though they had no idea what to expect from me. Most of all, I felt, they wanted to sincerely believe I wouldn’t jump up suddenly when they least expected, reach in three steps the terrace railing and vault over in a foolish effort to fly side by side with birds of an unknown species.

„Common swifts, a species always on the move,” the tallest guest cut through the silence. He was the only one there who seemed to have one more goal, armed as he was with a pair of huge binoculars, beaten by age, and which, at that very moment, were hanging down crooked, tugging at his neck with every movement. He had not used them and there was no reason to. Beside the seabirds, there wasn’t very much to be seen around here. The wide old world, the real version began in less than an hour by car in all directions.

Somewhere in that world, he was a museum director. His job was to know. Nothing more than that. And he knew.

„In ancient Greek, opous means ‘no feet,’ ” the museum head finally added, after a slight, but very visible deliberation. „I wonder where their nests are,” he added, and with a wide gesture embraced the entire left side of the house, all the way straight south. „Whoa! Where once there were only bald-headed hills, a few orchards and, I think, five church steeples, I see now wide boulevards, malls, garages, discos, and bazaars, hey, look, you’ve even put up two mosques in the middle to balance the view.”

„Yeah, yeah,” I said quietly. „Just like in a Thousand and One Nights. In any direction I look, I see something: to the front, the ocean; behind, the mountain; to the right, the forest; to the left, the bazaar. And now, dear kids, who do you think has just reached dead-center in this stunning live image, broadcast around the world? Take a peek, would you believe, it is me, traveling at leisure over this remarkable fairy tale with not one, but two nargilehs in my lap, while sitting cross-legged on the magical flying carpet. ”

„Watch out! With so many common swifts in the air at every ten yards, you’d surely hit at least seven of them on your first attempt at flying,” he smirked. “You might as well wipe your ass with your magical carpet.”

“We call them sea-swifts over here, not common swifts,” I interrupted. “Common sounds too common.”

“You may call them what you want, over here,” he answered. “Over there, it’s different. There aren’t any sea-swifts in any books. At most, sea-swallows, Sterna hirundo.”

“Well, many thanks for the precious information.”

“Whatever. Start a Rescue Center for birds, it would be worth it, even if this area is not what it was before, and there’s no sign it will ever come back to the before picture. I know exactly who you need to contact. Do you want me to arrange it in your name?”

I actually knew all that already, part of my research for The Tower. And I was perfectly happy without any of his connections, and, moreover, I did not want anyone to interfere in my life longer than needed. So, I mumbled something which wasn’t really words, then sat down heavily on a bench in the corner, keeping my feet at a right angle to the floor, and doing my best trying to avoid crossing them under me. I did not feel ready for another Turkish connotation. Somehow, through all that I managed to remain silent, but I knew my eyes were glowing as bright as can be.

Now that the natural order had been restored, and the true experts were finally in charge of the asylum, the atmosphere quickly defrosted. I had been put in the place I deserved. The rest of the group joined one by one the conversation, each contributing with the bits they knew about swifts.

The heaviest guest, the bank director, had recently been to Jerusalem and had seen there tiny nests hidden in the cracks of the Western Wall. „You know, in Hebrew it is called Kotel; it was once known as the Wailing Wall, a term the Israelis no longer use, as it implies too much mourning and they probably find that depressing.”

On top of everything, he had happened to arrive in Jerusalem on a festive day, when the Israeli authorities had organized in a square by the wall a welcome ceremony for the returning swifts. The banker even showed us a long clip on his humongous smartphone. I looked as well.

I supposed the Hebrew part of the ceremony had ended. Everything was proceeding in English, while the visitors from who knows where kept talking to each other. The mayor was there, a fat gent with a black yarmulke on his head, as well as was the deputy mayor, a lady wearing a bright red dress, on which small projectiles dropped from the sky at regular intervals had left lasting impressions. The woman kept earnestly smiling though, obviously aware of the long-held tradition that being a dropee brings everlasting luck. The so-called Rabbi of the Western Wall, who did not look at all like a rabbi, more like a sumo wrestler, repeated a few times what important place the Western Wall occupies in the Israeli history. In the end, not just him, but each of these three delivered in turn another long winded speech, which no one seemed to listen.

I liked the rabbi. He explained that in old Hebrew the name of the swifts was Kuus, and so the Kotel was a favorite Kuus motel since biblical times. He kept laughing in bursts as if all of the spectators were supposed to join him. It took a while until he was satisfied with the number of those who had joined them, and then all three hosts moved closer to each other, unfolding a bilingual welcome sign with enormous letters everyone (presumably the birds, too) could read from afar.

„As you have seen, the writing on the banner was only in Hebrew and English,” concluded gloomily my friend, picking up his smartphone. „There were six-seven hundred people assembled there in the square, of all nationalities. Some of us have protested: “Why bilingual, maybe we also care to know what the sign was saying. ”

“And maybe the swifts would have cared as well, and their numbers must have been in the thousands there, not just in the hundreds,” I thought immediately with an increasing agitation I could not explain. The mayor, his deputy, and the rabbi had managed to forget the swifts had come all the way from South Africa. It would not have been such a great deal to erect a sign for them as well, with a few, well-chosen words of encouragement in Afrikaans. After all, the word “Welcome” sounds and it is written about the same way in all Germanic languages.

Before, I wouldn’t hesitate to share such thoughts at once, and everything else going through my head at the moment. It was my signature, so to speak. I found out a long time ago that my friends were stimulated by having a nut in the group, and had enthusiastically encouraged me since I can remember. Runaway had been my nickname since high school and it stuck.

Of course, neither their placards, nor their linguistic contents had stirred me, but the ongoing discussion that had begun about them suddenly. The importance of the common swifts in culture and religion… How, for over two thousand years, they found shelter only on the west wall of the temple, an action symbolizing the divinity in both us and the birds, and how important it was for everyone present today which side of the wall they had chosen… It was the western wall and not the eastern—that had to be an omen.

„There is a program on Aevea TV, where the common swifts are very well described,” said the new director of the Chamber of Commerce, a well-known economist, who, like me, had published several books, although, obviously, about money and such.

„‘When they sit in their nests to lay eggs, that would be the only time they are, so to speak immobile; otherwise, they spend their life in the air, on the wing, eating small tasty insects, bathing in cool ponds, playing, drinking cold water, eating again, and they maybe moaning a little when meeting other swifts: everything is done in the greatest harmony found in the entire Lord’s Kingdom,’—that was what their expert told us.”

The economist finally concluded with the obvious satisfaction of someone who has shared something awesome with others, such as one of the secret seals hidden in the Statement of the State Chamber of Commerce’s manual. “Oh yes, they spend even the nights ‘on the wing,’ unless they find a porch or a church steeple at hand. In fact, their other expert assured us, they are the only known birds to even mate in the air.”

But didn’t the first expert implied that already? I wanted to ask,

The others started shaking their heads as vigorously as before, in all directions this time, as if each of them had a small metronome welded to their spines, and I was wondering what a big deal they had learned in 33 words to deserve so much enthusiasm.

I looked askance at the last visitor to arrive, the director of the University’s Ethics Department, who at the same time was a professor of theology at a neighboring seminary. He had not spoken a word since he had arrived. I was sure he had to preach or lecture a whole bunch of people just before, so very tired he seemed. I knew though, that, when necessary, he could speak as forcefully as the others, but always he remained the least aggressive.

In general, our ethics specialist was the person to find the balance point when our views promised to remain opposed all the way to infinity. He would patiently wait for us to conclude and then draw the conclusions. Even the director of the museum, the most socially prominent of the others, did not contradict him too often, and neither did I.

Besides, as far as I knew, the ethicist had recently become the ultimate authority for “What happens in a resuscitate/do not resuscitate dilemma,” for the entire region, the only one entrusted with the power to decide, “Are we keeping this guy tied up to his respirator, or we just switch it off?”

It always seemed a subject with so many answers, and it sure felt good to know each of us had such a friend.

This time, the great specialist in what’s right and what’s not found something to say about the swifts, although he had gone completely to the economist’s side after a few words:

„I often look at AeveaTV as well as at The LightTV. One day, an expert talked about their feathers, each of their shafts with 1,200 nerves fixed at the quill: swifts can modify the wing load by just lifting the barbs on the front edge. They can change the wing profile on the spot, something even the most advanced planes cannot do today.”

He looked at each of us and concluded: „That expert was a very convincing creationist. Does anyone here think the birds feathers had evolved from a reptile scales? Of course, that guy was right, not Darwin. Hey, did you know that the new Abu Dhabi Bird Hospital, right by the airport, is cleared now to transplant feathers? ”

No, the others did not know.

I knew, but I kept my mouth shut.

TURNUL

„Am scris povestirea aceasta, un mini-roman, se pare, „Turnul”, pentru că eu, în mod simbolic, vreau să rămân pe veci într-un turn.„Am scris povestirea aceasta, un mini-roman, se pare, „Turnul”, pentru că eu, în mod simbolic, vreau să rămân pe veci într-un turn.

„Am scris-o pentru că, spre deosebire de toți cei care au fugit care-ncotro dintr-un alt turn masiv de piatră, fără nici o legătură cu primul, dar, să zicem, în flăcări, eu aș fi rămas ca singurul voluntar, hotărât să salvez cele cinci animale bolnave încuiate la capătul labirintului de coridoare de la etajul doi.

„Am scris-o pentru că mă obsedează de mic să le arăt altora drumul, oriunde ar duce, și oricare ar fi consecințele, pentru că eu tind mereu să fiu primul care să-și dea drumul din vreun turn pe o funie, de exemplu. În jos, la stânga, la dreapta, ori încotro, nici nu contează unde, ba m-aș fi cățărat și înapoi la nevoie, cu condiția clară însă, de a fi lăsat în pace să îi ghidez pe toți spre salvare în maniera pe care o ştiu eu.”

Așa cum descoperisem din anii facultății, toți prietenii mei știau mult mai precis ca mine de ce scriu și, pe deasupra, cui exact încercam să mă adresez în scrierile mele—în mintea lor, eu îmi identificasem de multă vreme cititorii.

Niciunuia nu i-a trecut vreodată prin cap să-mi ofere un motiv mai simplu: scriu pentru că-mi place să scriu. Scriu ca să-mi dovedesc în primul rând mie că pot de unul singur să pun împreună o structură coerentă, care să aibă cap și coadă, care să pornească din nimic de la sol și să se înalțe spre cer fără alt sprijin decât paginile care se acumulează una peste alta. O catedrală de hârtie.

Ce mă mirase cel mai mult acum, această ultima dată, era că-mi oferiseră deja trei opinii atât de categorice, fără să fi citit un singur rând din ce scrisesem, bazându-se doar pe ce le spusesem la telefon că plănuiam să scriu, nu c-aș fi completat ceva, și-asta în condițiile în care eu însumi, pînă la acel punct, scrisesem vreo 10 pagini.

Am decis să schimb titlul. Nu voiam ca atenția cititorului potențial să fie trimeasă fără rost pe o potecă greșită. „Prințesa și Turnul” sună mai bine, mi-am zis. Este un titlu potrivit pentru o povestire de copii, în special fetițe, și cu siguranță mai plauzibil decât doar „Turnul.”

Ajunsese chiar să mi se pară caraghios titlul inițial. Nici nu mai eram sigur ce-mi trecuse prin cap la alegerea sa. Prințesa este protagonista povestirii de la prima pagină și-n nici-un caz Turnul. Apoi apare și ciulinul, care, deși mai mult un proiect până una-alta, și el are cu mult mai mult impact decât Turnul.

Oricum el și vorbește mult, cu mult mai mult, decât Turnul, care este, mai degrabă, taciturn.

De notat pentru mine era constatarea că, în continuare, prietenii mei nu pricepeau deloc ce-anume-mi face mintea să ticăie. Nici pe departe nu sunt eu chiar așa de obsedat de turnuri cum își închipuie ei.

Turnurile sunt structuri masive în care trăiesc permanent la diverse nivele o groază de oameni, sau dacă nu sunt locuibile, grupuri și mai mari se cațără câte-o oră-două pe terasa din vârf, se fâțâie preocupați prin colțuri, fac un milion de poze și scuipă înspre caldarâmul de jos, încercând fără rost să vadă cam pe unde le-aterizează saliva.

Ceea ce prețuiesc eu în schimb, este solitudinea. De aceea mă interesa mai mult o variantă simplificată de turn, ceea ce numim mai degrabă un foișor—asta chiar mă urmărea de mult, ideea foișoarelor în sine, deșim din nou, nu oricare din ele, ci unul cât mai svelt, cu un spațiu adecvat, dar spartan la vârf, fără înghesuială de scaune și mobilă. De altfel, cu ultimii mei bani mai serioși, îmi și construisem unul. Aproximativ.

„Am să servesc numai cafeluțe azi,” le-am spus după ce ne-am așezat la masa lungă de-afară, acoperită cu pagini îngrijit tipărite, dar zmângălite cu note mărunte pe margini. „Nimic altceva nu pare să funcționeze în casa asta decât cafetiera. Cred că-mi ajunge ce am prin cămară să fac trei cafeluțe la fiecare. Apoi vom sta la taifas.”

Au clătinat cu toții îngăduitor din cap, câțiva au și ridicat din umeri, în același stil, la unison. Sigur, păreau ei să spună. Numai cafeluțe. Trei, două, una. Zero. Câte or fi. Nici nu ne așteptam la altceva de la tine în clipa asta—astăzi. Și-n niciun caz cafea la nisip.

Dacă nu mai eram în stare să-mi servesc oaspeții în același stil de potentat oriental cu care îi obișnuisem cu doar trei-patru ani în urmă, priveliștea de pe terasa casei mele nu se schimbase prea mult și peste tot domnea o atmosferă de pace.

În față, pescăruși, cormorani, și câte un rar vultur de mare, se pendulau languros prin aer, înaintea unui picaj în masă până la oglinda apei, unde, depinzând de specializare, fie că plonjau năvalnic și dispăreau pe loc din vedere, fie că își schimbau în ultima clipă unghiul de atac, continuând o vreme îndelungată razant cu valurile, până ce săgetau deodată drept în sus, ca și cum cineva nevăzut îi gonea amenințător de la spate, intercalându-se apoi rând pe rând în formația mamă de la mare altitudine, unde, fără vreun efort aparent, reluau cu nepăsare dansul fără sfârșit de pe cer.

Surprinzător pentru mine, niciunul din prietenii mei nu se uita la păsările marine. Tot după zburătoare se uitau, însă privirile lor erau ațintite în spatele meu, undeva la dreapta. Nu era nevoie să întorc capul și să-mi chinuiesc gâtul la fel de beteag după trei operații—sechela mai ușor de observat a accidentului, pentru că era pe dinafară. Pe dinăuntru, ce să mai vorbim.

De vreo lună, un cârd numeros de rândunele-de-turn survola zgomotos în fiecare dimineață coridorul îngust dintre foișorul din spatele casei și piscul ascuțit, acoperit de zăpadă, al Muntelui Mare. În câteva secunde, rândunelele ajunseseră deja deasupra pădurii de brazi, aparent imobile la dreapta, ceea ce m-a mirat, căci un vânt rece începuse să sufle cu putere dis-de-dimineață și nu dădea vreun semn că se va încetini. Apoi au dispărut brusc din vedere, dar știam unde erau: se răspândiseră primprejur să vâneze insecte, după care vreo 11-12 obișnuiau să se agațe de gărdulețul alb din spate ca să-și digere în liniște câte un dumicat lipicios pentru puii care îi așteptau înfometați sus în cuiburi.

Eram la fel de convins că prietenii mei habar n-aveau la ce fel de păsărele se uitaseră preț de jumătate de minut. Așteptam răbdător să văd ce le mai trecea prin cap, doar că și eu mă simțeam la fel de atent observat de ei, și, dacă-i posibil, cu cel puțin aceeași răbdare. Nu păreau siguri de ce se puteau aștepta de la mine. Cel mai mult, ziceam eu, voiau să creadă sincer că n-am să sar deodată în sus și, după câțiva pași, să mă avânt peste balustrada terasei, într-un efort nesăbuit să zbor alături de-un cârd de păsări dintr-o specie necunoscută.

„Apus apus, o specie mereu pe drumuri,” a tăiat deodată tăcerea cel mai înalt dintre ei, singurul care venise în vizită de parcă mai avea un alt țel, înarmat cu un binoclu enorm, cam bătut de soartă, și care în acest moment îi atârna strâmb, hâțânându-se de gât la fiecare mișcare. Nu-l folosise încă și nici nu avea de ce. Nu rămăsese mare lucru de văzut pe aici. Lumea cea mare, lumea reală începea la nici o oră distanță cu mașina, în toate direcțiile.

Undeva pe-acolo, el era director de muzeu. Meseria lui era să știe. Atât. Şi chiar știa.

„În greaca veche, opous înseamnă ‘fără picioare,’” a adăugat în cele din urmă directorul, cu o undă fugară, dar foarte vizibilă de deliberare.

„Mă întreb unde au cuiburile,” și cu un gest larg îmbrățișă toată partea stângă, spre Sud, a casei. „Acolo unde înainte erau doar dealuri, livezi și cinci turle, acum văd bulevarde largi, malluri, discoteci și bazare, hei, uite, v-ați pus chiar și două moschei.”

„Da,” am zis eu sec. „Exact ca-ntr-o mie și-una de nopți. În orice direcție mă uit văd ceva: în față, oceanul; în spate, muntele; la dreapta, pădurea; la stânga, bazarul. Şi, dragi copii, cine credeți voi că apare acum în mijlocul acestui tablou vivant, zburând haiducește pe deasupra acestei priveliști de basm? Ia te uită, eu însumi, cu o narghilea în poală şi așezat turcește pe covorul fermecat.”

„Cu atâtea rândunele-de-turn prin preajmă, te-ai lovi cu siguranță de vreo șapte din ele la prima încercare de zbor, așa că poți să te ștergi la fund cu covorul tău fermecat. Deschideți şi voi pe-aici un Rescue Center pentru păsărele, ar merita, chiar dacă zona nu mai e ce-a fost înainte şi nici nu dă semne să-şi mai revină vreodată. Ştiu exact pe cine trebuie să contactezi. Vrei să-ți fac legătura?”

Ştiam și singur, fără vreuna din legăturile lui, și-n plus, nici nu voiam să se amestece oricine în viața mea mai mult decât era nevoie. Așa că am mormăit ceva nedeslușit, m-am așezat pe-un scaun într-un colț, normal, cu picioarele pe podea, nu turcește, și pe urmă am tăcut.

Acum, că se restabilise ordinea naturală și adevărații experți preluaseră fără efort conducerea azilului, iar eu fusesem pus la punct aşa cum meritam, atmosfera s-a dezghețat rapid. Restul grupului a intrat în conversație, fiecare contribuind cu ce mai știa despre rândunelele-de-turn.

Directorul de bancă fusese de curând la Ierusalim și văzuse acolo cuiburi ascunse în crăpăturile din Zidul de Vest, „care în ebraică se numește Kotel; odinioară era cunoscut ca Zidul Plângerilor, un termen care nu se mai folosește, cică implică prea multă boceală.”

Nimerise la Ierusalim într-o zi festivă, în care păsărilor li se organizase de către autorități o ceremonie de bun sosit în piața din fața zidului. Bancherul trăsese totul pe video și ne-a arătat un clip de-un minut pe smartfonul lui. M-am uitat și eu.

Probabil că partea în ebraică a ceremoniei se terminase, căci tot ce-am văzut era în engleză, și oricum privitorii erau turiști de pe cine știe unde.

Primarul, un ins gras cu o yarmulke pe cap, mare cât o șapcă, viceprimarul, o femeie ștearsă, îmbrăcată în roșu pe care tot ce pica din cer de la păsări se vedea imediat, și rabinul Zidului de Vest, care nu arăta deloc a rabin și nici n-aș fi știut ce căuta pe-acolo dacă n-ar fi repetat de câteva ori ce loc important ocupă Zidul de Vest în istoria Israelului. Până la umă, nu numai el, dar toți trei au ținut discursuri.

Mi-a plăcut rabinul. A explicat că în ebraica veche numele rândunelelor era kuus și deci Kotel era un motel preferat de Kuus, încă din Biblie, după care a râs prelung, ca și cum toți cei de față ar fi trebuit să i se alăture. A durat ceva, până a fost satisfăcut de numărul celor care i se alăturaseră, apoi toți trei s-au apropiat unul de altul și au desfășurat o pancartă bilingvă de bun venit cu litere enorme pe care toată lumea (probabil și păsărelele) să o poată citi de departe.

„Cum ați văzut și voi, scrisul pe pancartă era numai în ebraică și în engleză,” a încheiat prietenul meu după ce i-am înapoiat smartfonul. „Erau câteva sute de oameni acolo în piață, de toate naționalitățile. Unii dintre noi au protestat. Poate ne păsa și nouă să știm ce spunea semnul.”

Poate le-ar fi păsat și rândunelelor, iar ele trebuie să fi fost cu miile pe-acolo, nu doar cu sutele, m-am gândit agitat. Primarul, adjuncta lui și rabinul uitaseră cu desăvârșire că ele veneau tocmai din Africa de Sud. N-ar fi fost o mare scofală să le pună și lor un semn, două, cu câteva cuvinte de încurajare în afrikaans. Iar welcome, cel puțin, se scrie cam la fel în toate limbile germanice.

Altă dată n-aş fi ezitat să împărtăşesc asemenea gânduri, ca şi orice altceva îmi trecea prin cap. Era semnătura mea, ca să zic așa. Aveam demult impresia că prietenii mei erau stimulați să aibă un zănatec în grup şi mă încurajaseră cu entuziasm de când mi-aduc aminte. De fapt, Haihui îmi fusese porecla încă de la școală.

Bineînțeles că nu pancartele și nici conținutul lor lingvistic mă agitaseră pe mine, ci discuția începută pe neașteptate în privința lor.

Importanța rândunelelor-de-turn în cultură și religie.

Cum, de peste două mii de ani, ele își găsesc adăpost doar pe zidul de vest al templului, o acțiune simbolizând divinitatea și la noi și la păsărele, și cât de important era pentru toți ce parte din zid îşi aleseseră.

„Există un program la Aevea TV, unde rândunelele-de-turn sunt atât de bine descrise,” a zis emoționat directorul camerei de comerț, un economist cunoscut, care și el publicase câteva cărți—evident, toate de economie. „Ori stau în cuib să depună ouă, singurul loc unde ele s-ar găsi, ca să zicem aşa, imobile; ori îşi petrec tot timpul în aer, pe aripă, unde mâncă insecte gustoase, se scaldă în iazuri răcoroase, se mai şi joacă, beau apă rece, mănâncă iarăși, moțăie puțin, se întâlnesc cu alte rândunele-de-turn, eventual procrează, totul în cea mai mare armonie cu restul Împărăției Domnului

.„’Până și nopțile le pot petrece pe aripă, dacă nu cumva găsesc un foișor ori o turlă de biserică la îndemână și, de fapt, sunt singurele păsări cunoscute a se împerechea în zbor,’ așa zicea expertul lor,” a încheiat economistul cu satisfacția vădită a celui ce-a împărtăşit altora ceva nemaipomenit, ca de pildă unul din secretele pecetluite ascunse în manualul de funcționare a camerei de comerț a statului.

Ceilalți clătinau iarăşi cu toții din cap în toate direcțiile de parcă fiecăruia dintre ei îi fusese instalat un mic metronom în spinare, iar eu mă întrebam revoltat ce mare brânză aflaseră în 33 de cuvinte încât să merite atât de mult entuziasm.

M-am uitat întrebător spre ultimul vizitator sosit la întâlnire, directorul catedrei de etică a universității, care în acelaşi timp era și profesor de teologie la un seminar vecin. Nu scosese un cuvânt de când sosise. Eram sigur că trebuise să țină vreo predică ori vreo prelegere îndelungată cu puțin înainte, căci părea obosit. La nevoie, putea să vorbească la fel de mult ca și ceilalți în alte condiții, dar întotdeauna era cel mai puțin agresiv.

În general, specialistul nostru în etică era cel ce găsea punctul de echilibru al balanței când punctele noastre de vedere promiteau să rămână opuse tot drumul spre infinit. Aştepta cu răbdare să încheiem ciondănelile şi apoi oferea concluziile. Nici măcar directorul de muzeu, cel mai băgăreț dintre ceilalți, nu-l contrazicea prea des şi nici eu.

Pe deasupra, după câte știam, eticistul era și ultima autoritate pentru toată zona cu împuternicirea expresă să decidă ce se întâmplă cu cineva ajuns în stare vegetativă. „Mai ținem legat de aparate pe insul ăsta ori îi închidem pompa de respirat”— întotdeauna un subiect cu multe de spus, în care ne simțeam bine s-avem la o adică un astfel de prieten.

Și de data asta, marele specialist în ce-i drept și nu e găsise destule de spus despre rândunelele-de-turn, deși trecuse complet de partea economistului după câteva cuvinte:

„Mă uit şi eu destul de des la Aevea, ca și la Lumina, de altfel. Același expert a vorbit despre penele lor, cu 1200 de nervi fixaţi de rădăcină, așa că rândunelele îşi pot modifica portanța aripii ridicând puful de pe muchia din faţă. Își schimbă profilul aripii adică, ceva ce nici cele mai avansate avioane de azi nu pot s-o facă.” Expertul era un creaționist convins și a încheiat zicând, „Mai crede cineva că penele s-au dezvoltat din solzii reptilelor? Tipul ăla avea dreptate, nu Darwin. Hei, știați că la spitalul de păsări din Abu Dhabi se fac acum transplanturi de pene?”

Nu, ceilalți nu știau. Eu știam, dar mi-am ținut în continuare gura.